Climate change may expand suitable cropland, particularly in the Northern high latitudes, but tropical regions may becoming decreasingly suitable, according to a study published September 17, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Florian Zabel from Ludwig Maximilians University, Germany and colleagues.

Most of the Earth's accessible agricultural land are already under cultivation. Ecological factors such as climate, soil quality, water supply and topography determine the suitability of land for agriculture. Climate change may impact global agriculture, but some regions may benefit from it. In a new study, researchers focused on the probable impact of climate change on the supply of land suitable for the cultivation of the 16 major food and energy crops worldwide, including staples such as maize, rice, soybeans and wheat. They simulated the impact of climate change on agricultural production over the course of the 21st century and found that two-thirds of all land potentially suitable for agricultural use is already under cultivation.

The results indicate that climate change may expand the supply of cropland in the high latitudes of the Northern hemisphere, including Canada, Russia, China, over the next 100 years. However, in the absence of adaptation measures such as increased irrigation, the simulation projects a significant loss of suitable agricultural land in Mediterranean regions and in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. The land suitable for agricultural would be about 54 million km2 -- and of this, 91% is already under cultivation. "Much of the additional area is, however, at best only moderately suited to agricultural use, so the proportion of highly fertile land used for crop production will decrease," says Zabel. Moreover, in the tropical regions of Brazil, Asia and Central Africa, climate change will significantly reduce the chance of obtaining multiple harvests per year.

"In the context of current projections, which predict that the demand for food will double by the year 2050 as the result of population increase, our results are quite alarming. In addition, one must consider the prospect of increased pressure on land resources for the cultivation of forage crops and animal feed owing to rising demand for meat, and the expansion of land use for the production of bioenergy," says Zabel.

The Future of Global Agriculture May Include New Land, Fewer Harvests

Friday, September 19, 2014

Turbocharging Photosynthesis to Feed the World

Two down, one to go. Researchers have completed the second of three major steps needed to turbocharge photosynthesis in crops such as wheat and rice, something that could boost yields by around 36 to 60 percent for many plants. Because it’s more efficient, the new photosynthesis method could also cut the amount of fertilizer and water needed to grow food.

Researchers at Cornell University and Rothamsted Research in the United Kingdom successfully transplanted genes from a type of bacteria—called cyanobacteria—into tobacco plants, which are often used in research. The genes allow the plant to produce a more efficient enzyme for converting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into sugars and other carbohydrates. The results were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Scientists have long known that some plants are much more efficient at turning carbon dioxide into sugar than other plants. These fast-growing plants—called C4 plants—include corn and many types of weeds. But 75 percent of the world’s crops (known as C3 plants) use a slower and less efficient form of photosynthesis. Researchers have been attempting for a long time to change some C3 plants—including wheat, rice, and potatoes—into C4 plants. The approach has been given a boost lately by novel high-precision gene-editing technologies that are being applied to the C4 Rice Project (see “Why We Will Need Genetically Modified Foods”).

The Cornell and Rothamsted researchers took a simpler approach. Rather than attempting to convert a C3 plant into a C4 plant by changing its anatomy and adding new cell types and structures, the researchers modified components of existing cells. “If you can have a simpler mechanism that doesn’t require anatomical changes, that’s pretty darn good,” says Daniel Voytas, director of the Center for Genome Engineering at the University of Minnesota.

Turbocharging Photosynthesis to Feed the World

Researchers at Cornell University and Rothamsted Research in the United Kingdom successfully transplanted genes from a type of bacteria—called cyanobacteria—into tobacco plants, which are often used in research. The genes allow the plant to produce a more efficient enzyme for converting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into sugars and other carbohydrates. The results were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Scientists have long known that some plants are much more efficient at turning carbon dioxide into sugar than other plants. These fast-growing plants—called C4 plants—include corn and many types of weeds. But 75 percent of the world’s crops (known as C3 plants) use a slower and less efficient form of photosynthesis. Researchers have been attempting for a long time to change some C3 plants—including wheat, rice, and potatoes—into C4 plants. The approach has been given a boost lately by novel high-precision gene-editing technologies that are being applied to the C4 Rice Project (see “Why We Will Need Genetically Modified Foods”).

The Cornell and Rothamsted researchers took a simpler approach. Rather than attempting to convert a C3 plant into a C4 plant by changing its anatomy and adding new cell types and structures, the researchers modified components of existing cells. “If you can have a simpler mechanism that doesn’t require anatomical changes, that’s pretty darn good,” says Daniel Voytas, director of the Center for Genome Engineering at the University of Minnesota.

Turbocharging Photosynthesis to Feed the World

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Greenhouse Gases: New Group of Soil Micro-Organisms Can Contribute to Their Elimination

INRA research scientists in Dijon have shown that the ability of soils to eliminate N2O can mainly be explained by the diversity and abundance of a new group of micro-organisms that are capable of transforming it into atmospheric nitrogen (N2).

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a potent greenhouse gas that is also responsible for destroying the ozone layer. INRA research scientists in Dijon have shown that the ability of soils to eliminate N2O can mainly be explained by the diversity and abundance of a new group of micro-organisms that are capable of transforming it into atmospheric nitrogen (N2). These results, published in Nature Climate Change in September 2014, underline the importance of microbial diversity to the functioning of soils and the services they deliver.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is one of the principal greenhouse gases, alongside carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4); it is also responsible for destruction of the ozone layer. Terrestrial ecosystems contribute to about 70% of N2O emissions, at least 45% being linked to the nitrogen-containing products found in agricultural soils (fertilisers, slurry, manure, crop residues, etc.). "In order to lower emissions of N2O and develop more environmentally-friendly agriculture, it is important to understand the processes involved not only in its production but in its elimination," explain the scientists. This elimination can be achieved by micro-organisms living in the soil that are able to reduce N2O into nitrogen (N2), the gas that makes up around four-fifths of the air we breathe and which has no impact on the environment.

Greenhouse Gases: New Group of Soil Micro-Organisms Can Contribute to Their Elimination

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a potent greenhouse gas that is also responsible for destroying the ozone layer. INRA research scientists in Dijon have shown that the ability of soils to eliminate N2O can mainly be explained by the diversity and abundance of a new group of micro-organisms that are capable of transforming it into atmospheric nitrogen (N2). These results, published in Nature Climate Change in September 2014, underline the importance of microbial diversity to the functioning of soils and the services they deliver.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is one of the principal greenhouse gases, alongside carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4); it is also responsible for destruction of the ozone layer. Terrestrial ecosystems contribute to about 70% of N2O emissions, at least 45% being linked to the nitrogen-containing products found in agricultural soils (fertilisers, slurry, manure, crop residues, etc.). "In order to lower emissions of N2O and develop more environmentally-friendly agriculture, it is important to understand the processes involved not only in its production but in its elimination," explain the scientists. This elimination can be achieved by micro-organisms living in the soil that are able to reduce N2O into nitrogen (N2), the gas that makes up around four-fifths of the air we breathe and which has no impact on the environment.

Greenhouse Gases: New Group of Soil Micro-Organisms Can Contribute to Their Elimination

Sunday, August 10, 2014

Lake Erie's Algae Explosion Blamed on Farmers

Ultimately, algae blooms are caused by excess phosphorus in the water that provides the algae with the fertilizer it needs to grow exponentially, given enough sun and warm enough water temperatures. But the source of that phosphorus can vary.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, said Glenn Benoy, a senior water quality specialist and science adviser with the International Joint Commission. the main source of phosphorus was sewage plants. The algae problem was considered so serious that communities on the shores of the lake poured billions of dollars into sewage infrastructure upgrades and implemented laws banning phosphorus in laundry detergents.

This time the main problems are thought to be ones that governments have much less direct control over. To some extent, they include the application of fertilizers to lawns and golf courses, growing expanses of pavement in urban areas that cause water to drain more quickly into waterways without being filtered by vegetation, and invasive zebra mussels that release extra nutrients into the water as they feed. But those aren't thought to be the biggest cause.

"We think farming is the major culprit behind the current levels of phosphorus that's in runoff and the phosphorus loads that are getting dumped into the western basin of Lake Erie," Benoy told CBC News.

The commission's report suggested that changes to farming practices were largely to blame for recent blooms.

"The main changes that are responsible have to do with intensification of farming – getting more out of the land than we did historically," Benoy said, adding that that includes things like:

As a result, companies sometimes offer discounts to farmers who buy and apply their fertilizer to the surface of their fields in the fall – a practice that appears to significantly increase the rate at which it gets washed into local waterways.

The algae problem in Lake Erie that fouled the water that hundreds of thousands of people rely on for drinking, cooking and bathing last week was thought to have been successfully eliminated in the 1980s. Farming is the main culprit today, and climate change has become an "aggravating factor."

Lake Erie's Algae Explosion Blamed on Farmers

From the 1960s to the 1980s, said Glenn Benoy, a senior water quality specialist and science adviser with the International Joint Commission. the main source of phosphorus was sewage plants. The algae problem was considered so serious that communities on the shores of the lake poured billions of dollars into sewage infrastructure upgrades and implemented laws banning phosphorus in laundry detergents.

This time the main problems are thought to be ones that governments have much less direct control over. To some extent, they include the application of fertilizers to lawns and golf courses, growing expanses of pavement in urban areas that cause water to drain more quickly into waterways without being filtered by vegetation, and invasive zebra mussels that release extra nutrients into the water as they feed. But those aren't thought to be the biggest cause.

"We think farming is the major culprit behind the current levels of phosphorus that's in runoff and the phosphorus loads that are getting dumped into the western basin of Lake Erie," Benoy told CBC News.

The commission's report suggested that changes to farming practices were largely to blame for recent blooms.

"The main changes that are responsible have to do with intensification of farming – getting more out of the land than we did historically," Benoy said, adding that that includes things like:

- More livestock farming and greater application of their waste to fields.

- Higher application of fertilizers in general.

- An increase in corn farming in the U.S. Midwest, partly to meet a demand for ethanol fuel.

As a result, companies sometimes offer discounts to farmers who buy and apply their fertilizer to the surface of their fields in the fall – a practice that appears to significantly increase the rate at which it gets washed into local waterways.

The algae problem in Lake Erie that fouled the water that hundreds of thousands of people rely on for drinking, cooking and bathing last week was thought to have been successfully eliminated in the 1980s. Farming is the main culprit today, and climate change has become an "aggravating factor."

Lake Erie's Algae Explosion Blamed on Farmers

Thursday, August 7, 2014

Effects of Poisonous Algae on the Nation's Water Supply - The Diane Rehm Show

Large blooms of poisonous algae in Lake Erie recently forced a tap water ban in Toledo, Ohio. Scientists say it's a widespread problem across the country. Diane and her guests discuss what's behind the increase in harmful algae and debate over tougher regulation.

Effects of Poisonous Algae on the Nation's Water Supply - The Diane Rehm Show

Effects of Poisonous Algae on the Nation's Water Supply - The Diane Rehm Show

Tuesday, August 5, 2014

State Department of Agriculture Cracks Down on Seed Libraries

It was a letter officials with the Cumberland County Library System were surprised to receive.

The system had spent some time working in partnership with the Cumberland County Commission for Women and getting information from the local Penn State Ag Extension office to create a pilot seed library at Mechanicsburg’s Joseph T. Simpson Public Library.

The effort was a new seed-gardening initiative that would allow for residents to “borrow” seeds and replace them with new ones harvested at the end of the season.

Through researching other efforts and how to start their own, Cumberland County Library System Executive Director Jonelle Darr said Thursday that no one ever came across information that indicated anything was wrong with the idea. Sixty residents had signed up for the seed library in Mechanicsburg, and officials thought it could grow into something more.

That was, until the library system received a letter from the state Department of Agriculture telling them they were in violation of the Seed Act of 2004.

Darr explained that the Seed Act primarily focuses on the selling of seeds — which the library was not doing — but there is also a concern about seeds that may be mislabeled (purposefully or accidentally), the growth of invasive plant species, cross-pollination and poisonous plants.

The department told the library it could not have the seed library unless its staff tested each seed packet for germination and other information. Darr said that was clearly not something staff could handle.

Though the seed library is no longer an option, Darr said the department has left it open to the library to host “seed swap” days where private individuals can meet and exchange seeds. As long as the library system itself is not accepting seeds as donations, Darr said such an event would meet the requirements of the act.

State Department of Agriculture Cracks Down on Seed Libraries

The system had spent some time working in partnership with the Cumberland County Commission for Women and getting information from the local Penn State Ag Extension office to create a pilot seed library at Mechanicsburg’s Joseph T. Simpson Public Library.

The effort was a new seed-gardening initiative that would allow for residents to “borrow” seeds and replace them with new ones harvested at the end of the season.

Through researching other efforts and how to start their own, Cumberland County Library System Executive Director Jonelle Darr said Thursday that no one ever came across information that indicated anything was wrong with the idea. Sixty residents had signed up for the seed library in Mechanicsburg, and officials thought it could grow into something more.

That was, until the library system received a letter from the state Department of Agriculture telling them they were in violation of the Seed Act of 2004.

Darr explained that the Seed Act primarily focuses on the selling of seeds — which the library was not doing — but there is also a concern about seeds that may be mislabeled (purposefully or accidentally), the growth of invasive plant species, cross-pollination and poisonous plants.

The department told the library it could not have the seed library unless its staff tested each seed packet for germination and other information. Darr said that was clearly not something staff could handle.

Though the seed library is no longer an option, Darr said the department has left it open to the library to host “seed swap” days where private individuals can meet and exchange seeds. As long as the library system itself is not accepting seeds as donations, Darr said such an event would meet the requirements of the act.

State Department of Agriculture Cracks Down on Seed Libraries

Farming Reforms Offer Hope for Iran's Water Crisis

"Water scarcity poses the most severe human security challenge in Iran today," said Gary Lewis, United Nations Resident Coordinator for Iran.

The cause of the crisis is not in residential use; agriculture accounts for about 90 percent of water consumption, with much of it being used inefficiently.

Government figures show that only a third of agricultural water use is efficient, say U.N. officials. This inefficient management stretches across Iran and other countries in the region, including neighboring Iraq and Afghanistan where wars make it difficult to tackle environmental issues.

Major rivers in the cities of Isfahan and Shiraz, and on Iran's border with Afghanistan, have dried up. The depletion of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq has contributed to other environmental problems such as dust and sand storms.

With government policies mired in bureaucracy, the U.N. has offered to help. In 2012, the world body launched a pilot program to work with farmers near Lake Orumieh.

Farmers learned how to make compost, switched to organic-based fertilisers and attended weekly classes on water management which led to a 35 percent drop in consumption.

The new techniques have also allowed farmers to reduce costs and increase variety of crops from just wheat and beets to add maize, squash, onions and tomatoes.

Farming Reforms Offer Hope for Iran's Water Crisis

The cause of the crisis is not in residential use; agriculture accounts for about 90 percent of water consumption, with much of it being used inefficiently.

Government figures show that only a third of agricultural water use is efficient, say U.N. officials. This inefficient management stretches across Iran and other countries in the region, including neighboring Iraq and Afghanistan where wars make it difficult to tackle environmental issues.

Major rivers in the cities of Isfahan and Shiraz, and on Iran's border with Afghanistan, have dried up. The depletion of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq has contributed to other environmental problems such as dust and sand storms.

With government policies mired in bureaucracy, the U.N. has offered to help. In 2012, the world body launched a pilot program to work with farmers near Lake Orumieh.

Farmers learned how to make compost, switched to organic-based fertilisers and attended weekly classes on water management which led to a 35 percent drop in consumption.

The new techniques have also allowed farmers to reduce costs and increase variety of crops from just wheat and beets to add maize, squash, onions and tomatoes.

Farming Reforms Offer Hope for Iran's Water Crisis

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Climate Change: Soil Respiration Releases Carbon

The planet's soil releases about 60 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere each year, which is far more than that released by burning fossil fuels. This happens through a process called soil respiration. This enormous release of carbon is balanced by carbon coming into the soil system from falling leaves and other plant matter, as well as by the underground activities of plant roots.

Short-term warming studies have documented that rising temperatures increase the rate of soil respiration. As a result, scientists have worried that global warming would accelerate the decomposition of carbon in the soil, and decrease the amount of carbon stored there. If true, this would release even more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, where it would accelerate global warming.

New work by a team of scientists including Carnegie's Greg Asner and Christian Giardina of the U.S. Forest Service used an expansive whole-ecosystem study, the first of its kind, on tropical montane wet forests in Hawaii to sort through the many processes that control soil carbon stocks with changing temperature. Their work is published in Nature Climate Change.

The team revealed that higher temperatures increased the amount of leaf litter falling onto the soil, as well as other underground sources of carbon such as roots. Surprisingly, long-term warming had little effect on the overall storage of carbon in the tropical forest soil or the rate at which that carbon is processed into carbon dioxide.

Climate Change: Soil Respiration Releases Carbon

Short-term warming studies have documented that rising temperatures increase the rate of soil respiration. As a result, scientists have worried that global warming would accelerate the decomposition of carbon in the soil, and decrease the amount of carbon stored there. If true, this would release even more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, where it would accelerate global warming.

New work by a team of scientists including Carnegie's Greg Asner and Christian Giardina of the U.S. Forest Service used an expansive whole-ecosystem study, the first of its kind, on tropical montane wet forests in Hawaii to sort through the many processes that control soil carbon stocks with changing temperature. Their work is published in Nature Climate Change.

The team revealed that higher temperatures increased the amount of leaf litter falling onto the soil, as well as other underground sources of carbon such as roots. Surprisingly, long-term warming had little effect on the overall storage of carbon in the tropical forest soil or the rate at which that carbon is processed into carbon dioxide.

Climate Change: Soil Respiration Releases Carbon

Monday, July 28, 2014

What's Eating America: Corn is one of the plant kingdom's biggest successes. That's not necessarily good for the United States. - by Michael Pollan

F1 hybrid corn is the greediest of plants, consuming more fertilizer than any other crop. Though F1 hybrids were introduced in the 1930s, it wasn't until they made the acquaintance of chemical fertilizers in the 1950s that corn yields exploded. The discovery of synthetic nitrogen changed everything—not just for the corn plant and the farm, not just for the food system, but also for the way life on earth is conducted.

All life depends on nitrogen; it is the building block from which nature assembles amino acids, proteins and nucleic acid; the genetic information that orders and perpetuates life is written in nitrogen ink. But the supply of usable nitrogen on earth is limited. Although earth's atmosphere is about 80 percent nitrogen, all those atoms are tightly paired, nonreactive and therefore useless; the 19th-century chemist Justus von Liebig spoke of atmospheric nitrogen's "indifference to all other substances." To be of any value to plants and animals, these self-involved nitrogen atoms must be split and then joined to atoms of hydrogen.

Chemists call this process of taking atoms from the atmosphere and combining them into molecules useful to living things "fixing" that element. Until a German Jewish chemist named Fritz Haber figured out how to turn this trick in 1909, all the usable nitrogen on earth had at one time been fixed by soil bacteria living on the roots of leguminous plants (such as peas or alfalfa or locust trees) or, less commonly, by the shock of electrical lightning, which can break nitrogen bonds in the air, releasing a light rain of fertility.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

U.S. Midwestern Farmers Fighting Explosion of 'Superweeds'

Farmers in important crop-growing states should consider the environmentally unfriendly practice of deeply tilling fields to fight a growing problem with invasive "superweeds" that resist herbicides and choke crop yields, agricultural experts said this week.

Resistance to glyphosate, the main ingredient in widely used Roundup herbicide, has reached the point that row crop farmers in the Midwest are struggling to contain an array of weeds, agronomists say.

Extreme controls are needed to fight herbicide-resistant weeds in some areas, University of Missouri weed scientist Kevin Bradley said in a report to farmers. One particularly aggressive weed that can grow 1-2 inches a day is Palmer amaranth.

He said farmers facing extreme out-of-control weeds should try deep tillage, a practice that removes weeds but can also lead to soil erosion and other environmental concerns.

Farmers moved away from heavy tillage of the land decades ago, and the more sustainable 'no-till' farming has become the norm. But it relies on heavy use of herbicides like glyphosate, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture says 70 million acres of U.S. farmland had glyphosate resistant weeds in 2013.

U.S. Midwestern Farmers Fighting Explosion of 'Superweeds'

Resistance to glyphosate, the main ingredient in widely used Roundup herbicide, has reached the point that row crop farmers in the Midwest are struggling to contain an array of weeds, agronomists say.

Extreme controls are needed to fight herbicide-resistant weeds in some areas, University of Missouri weed scientist Kevin Bradley said in a report to farmers. One particularly aggressive weed that can grow 1-2 inches a day is Palmer amaranth.

He said farmers facing extreme out-of-control weeds should try deep tillage, a practice that removes weeds but can also lead to soil erosion and other environmental concerns.

Farmers moved away from heavy tillage of the land decades ago, and the more sustainable 'no-till' farming has become the norm. But it relies on heavy use of herbicides like glyphosate, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture says 70 million acres of U.S. farmland had glyphosate resistant weeds in 2013.

U.S. Midwestern Farmers Fighting Explosion of 'Superweeds'

Friday, July 18, 2014

How Existing Cropland Could Feed Billions More

Feeding a growing human population without increasing stresses on Earth's strained land and water resources may seem like an impossible challenge. But according to a new report by researchers at the University of Minnesota's Institute on the Environment, focusing efforts to improve food systems on a few specific regions, crops and actions could make it possible to both meet the basic needs of 3 billion more people and decrease agriculture's environmental footprint.

The report, published Thursday in Science, focuses on 17 key crops that produce 86 percent of the world's crop calories and account for most irrigation and fertilizer consumption on a global scale. It proposes a set of key actions in three broad areas that that have the greatest potential for reducing the adverse environmental impacts of agriculture and boosting our ability meet global food needs. For each, it identifies specific "leverage points" where nongovernmental organizations, foundations, governments, businesses and citizens can target food-security efforts for the greatest impact. The biggest opportunities cluster in six countries -- China, India, U.S., Brazil, Indonesia and Pakistan -- along with Europe.

How Existing Cropland Could Feed Billions More

The report, published Thursday in Science, focuses on 17 key crops that produce 86 percent of the world's crop calories and account for most irrigation and fertilizer consumption on a global scale. It proposes a set of key actions in three broad areas that that have the greatest potential for reducing the adverse environmental impacts of agriculture and boosting our ability meet global food needs. For each, it identifies specific "leverage points" where nongovernmental organizations, foundations, governments, businesses and citizens can target food-security efforts for the greatest impact. The biggest opportunities cluster in six countries -- China, India, U.S., Brazil, Indonesia and Pakistan -- along with Europe.

How Existing Cropland Could Feed Billions More

Thursday, July 17, 2014

'Peak Soil' Threatens Future Global Food Security

The challenge of ensuring future food security as populations grow and diets change has its roots in soil, but the increasing degradation of the earth's thin skin is threatening to push up food prices and increase deforestation.

While the worries about peaking oil production have been eased by fresh sources released by hydraulic fracturing, concern about the depletion of the vital resource of soil is moving center stage.

John Crawford, Director of the Sustainable Systems Program in Rothamsted Research in England said:

Such factors, exacerbated by climate change, can ultimately lead to desertification, which in parts of China is partly blamed for the yellow dust storms that can cause hazardous pollution in Asia, sometimes even severe enough to cross the Pacific Ocean and reduce visibility in the western United States.

Arable land in areas varying from the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa, to the Middle East and Northern China has already been lost due to soil degradation.

The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that 25 percent of agricultural land is highly degraded, while a further 8 percent is moderately degraded.

'Peak Soil' Threatens Future Global Food Security

While the worries about peaking oil production have been eased by fresh sources released by hydraulic fracturing, concern about the depletion of the vital resource of soil is moving center stage.

John Crawford, Director of the Sustainable Systems Program in Rothamsted Research in England said:

We know far more about the amount of oil there is globally and how long those stocks will last than we know about how much soil there is.Surging food consumption has led to more intensive production, overgrazing and deforestation, all of which can strip soil of vital nutrients and beneficial micro-organisms, reduce its ability to hold water and make it more vulnerable to erosion.

Under business as usual, the current soils that are in agricultural production will yield about 30 percent less than they would do otherwise by around 2050.

Such factors, exacerbated by climate change, can ultimately lead to desertification, which in parts of China is partly blamed for the yellow dust storms that can cause hazardous pollution in Asia, sometimes even severe enough to cross the Pacific Ocean and reduce visibility in the western United States.

Arable land in areas varying from the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa, to the Middle East and Northern China has already been lost due to soil degradation.

The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that 25 percent of agricultural land is highly degraded, while a further 8 percent is moderately degraded.

'Peak Soil' Threatens Future Global Food Security

Monday, July 14, 2014

The Soil Pollution Crisis in China: Cleanup Presents Daunting Challenge

Recent research findings have brought some rays of hope to China’s beleaguered soil. The Foshan Jinkuizi Plant Nutrition Company claims to have developed a soil remediation technology specifically designed for China’s heavy-metal polluted soil: a microorganism that can change the ionic state of heavy metals in the soil, deactivating the pollutants so they do not harm crops. The company claims that the method is cheap, convenient, easy to use, does not produce any secondary pollution, and is already in commercial production and use.

In another possible breakthrough, in April the Guangdong Geoanalysis Research Center announced a new product, Mont-SH6, which it says is a powerful absorber of toxic heavy metals such as cadmium, lead, mercury, copper, and zinc. Liu Wenhua, chief engineer at the center, claims that the product can reduce soil cadmium levels by over 90 percent, and that materials and manufacturing costs are low: remediation of 1.48 acres of cadmium-contaminated rice fields with this technique costs about $4,800. Mass production, according to Liu Wenhua, could bring this down to between $320 and $480.

The Soil Pollution Crisis in China: Cleanup Presents Daunting Challenge

In another possible breakthrough, in April the Guangdong Geoanalysis Research Center announced a new product, Mont-SH6, which it says is a powerful absorber of toxic heavy metals such as cadmium, lead, mercury, copper, and zinc. Liu Wenhua, chief engineer at the center, claims that the product can reduce soil cadmium levels by over 90 percent, and that materials and manufacturing costs are low: remediation of 1.48 acres of cadmium-contaminated rice fields with this technique costs about $4,800. Mass production, according to Liu Wenhua, could bring this down to between $320 and $480.

The Soil Pollution Crisis in China: Cleanup Presents Daunting Challenge

Friday, July 4, 2014

Thomas Jefferson: ‘Intergenerational Equity’ and Topsoil Depletion

The most succinct, systematic treatment of intergenerational principles left to us by the founders is that which was provided by Thomas Jefferson in his famous September 6, 1789 letter to James Madison. The letter was Jefferson’s final installment in a two year correspondence with Madison on the proposed Bill of Rights. Given the importance of this letter as background material for the bill of rights, and its independent value as a brilliant statement of intergenerational equity principles, it serves as the natural starting point for a discussion of the founders’ views on specific intergenerational issues.

Jefferson begins his letter by asserting that:

The contemporary issue to which Jefferson’s arguments most literally apply is the problem of topsoil depletion. As a planter in predominantly agrarian Virginia, who tended to view wealth as the direct or indirect product of the earth, it was natural for Jefferson to phrase his discussions of intergenerational relations — even intergenerational economic relations — in terms of soil:

Generational Sovereignty and the Land – The Earth as Tenancy-in-Common - Thomas Jefferson's Usufruct, part 2

Jefferson begins his letter by asserting that:

The question [w]hether one generation of men has a right to bind another … is a question of such consequences as not only to merit decision, but place also among the fundamental principles of every government…. I set out on this ground, which I suppose to be self-evident, ‘that the earth belongs in usufruct to the living’ ….Generational Sovereignty and the Land – The Earth as Tenancy-in-Common - Thomas Jefferson's Usufruct, part 1 (part 2 below)

The contemporary issue to which Jefferson’s arguments most literally apply is the problem of topsoil depletion. As a planter in predominantly agrarian Virginia, who tended to view wealth as the direct or indirect product of the earth, it was natural for Jefferson to phrase his discussions of intergenerational relations — even intergenerational economic relations — in terms of soil:

Are [later generations] bound to acknowledge [a national debt created to satisfy short-term interests], to consider the preceding generation as having had a right to eat up the whole soil of their country, in the course of a life….? Every one will say no; that the soil is the gift of God to the living, as much as it had been to the deceased generation; and that the laws of nature impose no obligation on them to pay this debt.Jefferson asserts that each generation has the right to inherit, undiminished, the same topsoil capital that its predecessors enjoyed. Our society’s failure to recognize and defend this most basic principle of intergenerational fairness during the past century has resulted in topsoil depletion that has reached crisis proportions. Soon we may have literally and irreparably “eaten up the whole soil of our country.”

Generational Sovereignty and the Land – The Earth as Tenancy-in-Common - Thomas Jefferson's Usufruct, part 2

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Invasive Plants Can Release Soil Carbon, Accelerate Global Warming

In a paper published in the scientific journal New Phytologist, plant ecologist Nishanth Tharayil and graduate student Mioko Tamura show that invasive plants can accelerate the greenhouse effect by releasing carbon stored in soil into the atmosphere.

Since soil stores more carbon than both the atmosphere and terrestrial vegetation combined, the repercussions for how we manage agricultural land and ecosystems to facilitate the storage of carbon could be dramatic.

In their study, Tamura and Tharayil examined the impact of encroachment of Japanese knotweed and kudzu, two of North America's most widespread invasive plants, on the soil carbon storage in native ecosystems.

"Our findings highlight the capacity of invasive plants to effect climate change by destabilizing the carbon pool in soil and shows that invasive plants can have profound influence on our understanding to manage land in a way that mitigates carbon emissions," Tharayil said.

Tharayil estimates that kudzu invasion results in the release of 4.8 metric tons of carbon annually, equal to the amount of carbon stored in 11.8 million acres of U.S. forest.

Invasive Plants Can Release Soil Carbon, Accelerate Global Warming

Since soil stores more carbon than both the atmosphere and terrestrial vegetation combined, the repercussions for how we manage agricultural land and ecosystems to facilitate the storage of carbon could be dramatic.

In their study, Tamura and Tharayil examined the impact of encroachment of Japanese knotweed and kudzu, two of North America's most widespread invasive plants, on the soil carbon storage in native ecosystems.

"Our findings highlight the capacity of invasive plants to effect climate change by destabilizing the carbon pool in soil and shows that invasive plants can have profound influence on our understanding to manage land in a way that mitigates carbon emissions," Tharayil said.

Tharayil estimates that kudzu invasion results in the release of 4.8 metric tons of carbon annually, equal to the amount of carbon stored in 11.8 million acres of U.S. forest.

Invasive Plants Can Release Soil Carbon, Accelerate Global Warming

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Straw Albedo Mitigates Extreme Heat

Fields that are not tilled after crop harvesting reflect a greater amount of solar radiation than tilled fields. This phenomenon can reduce temperatures in heat waves by as much as 2 °C, as researchers have demonstrated in a recent study.

Straw Albedo Mitigates Extreme Heat

Straw Albedo Mitigates Extreme Heat

Thursday, June 19, 2014

Scientists Look to Bacteria to Protect Crop Yields in the Face of Climate Change

Plants are often thought of as the masters of photosynthesis, the process by which sunlight, carbon dioxide and water are converted into usable energy, but when it comes to efficiency, they are beaten out by a rather surprising rival: bacteria.

Plants use resources, such as minerals and water, to promote their growth, but they also are restrained by the enzymes they need to complete photosynthesis, particularly an enzyme commonly known as RuBisCo.

Both plants and bacteria rely on RuBisCo to fix, or transform, carbon dioxide in the initial stages of photosynthesis. Unfortunately, RuBisCo can also react with oxygen, creating an unusable molecule that the plant must spend further energy to recycle. The result wastes far more nutrients than the plants need, costing both resources and money, and places a theoretical limit on crop yields.

Recently, research teams from Cornell University and Rothamsted Research in the United Kingdom began looking for ways around this barrier. They selected genes from bacteria that have evolved a way to bypass this dilemma and inserted them into plant cells, hoping that the bacterial addition would bestow the same advantages onto plants and provide food crops a way to boost yields under the pressures imposed by climate change.

"If proved effective, this technology would decrease the amount of key nutrients like nitrogen and, most notably, water needed by the plant, while increasing the yield," said Lin Myat, a postdoctoral fellow of molecular biology and genetics at Cornell and lead on the study. Both nutrients are valuable additions to any crop plant, especially under the pressure of increasing droughts.

In some key food crops, such as wheat or rice, the unwanted RuBisCo reaction happens roughly one-quarter of the time. While some crop plants like corn have devised ways to reduce the likeliness of this wasteful reaction, they require additional energy to do so. With a growing population to feed and limited resources, finding new ways to avoid the RuBisCo problem without expending extra energy in crop plants has become an increasingly studied topic.

Scientists Look to Bacteria to Protect Crop Yields in the Face of Climate Change

Plants use resources, such as minerals and water, to promote their growth, but they also are restrained by the enzymes they need to complete photosynthesis, particularly an enzyme commonly known as RuBisCo.

Both plants and bacteria rely on RuBisCo to fix, or transform, carbon dioxide in the initial stages of photosynthesis. Unfortunately, RuBisCo can also react with oxygen, creating an unusable molecule that the plant must spend further energy to recycle. The result wastes far more nutrients than the plants need, costing both resources and money, and places a theoretical limit on crop yields.

Recently, research teams from Cornell University and Rothamsted Research in the United Kingdom began looking for ways around this barrier. They selected genes from bacteria that have evolved a way to bypass this dilemma and inserted them into plant cells, hoping that the bacterial addition would bestow the same advantages onto plants and provide food crops a way to boost yields under the pressures imposed by climate change.

"If proved effective, this technology would decrease the amount of key nutrients like nitrogen and, most notably, water needed by the plant, while increasing the yield," said Lin Myat, a postdoctoral fellow of molecular biology and genetics at Cornell and lead on the study. Both nutrients are valuable additions to any crop plant, especially under the pressure of increasing droughts.

In some key food crops, such as wheat or rice, the unwanted RuBisCo reaction happens roughly one-quarter of the time. While some crop plants like corn have devised ways to reduce the likeliness of this wasteful reaction, they require additional energy to do so. With a growing population to feed and limited resources, finding new ways to avoid the RuBisCo problem without expending extra energy in crop plants has become an increasingly studied topic.

Scientists Look to Bacteria to Protect Crop Yields in the Face of Climate Change

Monday, June 2, 2014

How Nature Affects the Carbon Cycle

In 2011 more than half of the terrestrial world’s carbon uptake was in the southern hemisphere – which is unexpected because most of the planet’s land surface is in the northern hemisphere – and 60% of this was in Australia.

That is, after a procession of unusually rainy years, and catastrophic flooding, the vegetation burst forth and the normally empty arid center of Australia bloomed. Vegetation cover expanded by 6%.

Human activity now puts 10 billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere annually, and vegetation in 2011 mopped up 4.1 billion tonnes of that, mostly in Australia.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty about the carbon cycle and how the soils and the trees manage the extra carbon. Nobody knows what will happen to this extra carbon now in the hot dry landscapes of Australia: will it be tucked away in the soil? Will it be returned to the atmosphere by subsequent bushfires?

As scientists are fond of saying, more research is necessary.

How Nature Affects the Carbon Cycle

That is, after a procession of unusually rainy years, and catastrophic flooding, the vegetation burst forth and the normally empty arid center of Australia bloomed. Vegetation cover expanded by 6%.

Human activity now puts 10 billion tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere annually, and vegetation in 2011 mopped up 4.1 billion tonnes of that, mostly in Australia.

There remains a great deal of uncertainty about the carbon cycle and how the soils and the trees manage the extra carbon. Nobody knows what will happen to this extra carbon now in the hot dry landscapes of Australia: will it be tucked away in the soil? Will it be returned to the atmosphere by subsequent bushfires?

As scientists are fond of saying, more research is necessary.

How Nature Affects the Carbon Cycle

Monday, May 12, 2014

Iowa Is Getting Sucked into Scary Vanishing Gullies

A challenge for Iowa is the largely invisible crisis of topsoil, which appears to be eroding at a much higher rate than US Department of Agriculture numbers indicate—and, more importantly, at up to 16 times the natural soil replacement rate.

That disturbing assessment comes from Richard Cruse, an agronomist and the director of Iowa State University's Iowa Water Center. Cruse's on-the-ground research has shown a particular kind of soil erosion clearly connected to last year's heavy rains. Cruse told me that with current methods, the USDA measures a kind of soil loss called "sheet and rill erosion," wherein water washes soil away in small channels that form at the soil surface during rains. Under that measure, Iowa farmland loses an average 5.2 tons of topsoil per acre every year, according to the USDA's latest numbers, which are from 2007.

The USDA sees five tons per acre as a "magic number," Cruse said, because it's generally accepted to be the rate at which soil renews itself. So the prevailing view has been that "if we can limit erosion to five tons per acre, we can do this forever," Cruse said. But he added that the "best science" indicates that the real sustainable erosion rate is closer to a half ton per acre—meaning that even by the USDA's own limited measure, Iowa's soils are eroding much faster than they can be replaced naturally.

But here's where we get to the scary part. Using stereo-photographic techniques, Cruse and his team have been measuring a different form of erosion that occurs through what are known as "ephemeral gullies"—that is, large gashes in farm fields formed by water during heavy rains, bearing soil rapidly away and dispersing it into streams and rivers. This kind of erosion is not included in conventional soil-loss measures, and as a result, the USDA is "way underestimating" erosion in Iowa, he said.

Iowa Is Getting Sucked into Scary Vanishing Gullies

That disturbing assessment comes from Richard Cruse, an agronomist and the director of Iowa State University's Iowa Water Center. Cruse's on-the-ground research has shown a particular kind of soil erosion clearly connected to last year's heavy rains. Cruse told me that with current methods, the USDA measures a kind of soil loss called "sheet and rill erosion," wherein water washes soil away in small channels that form at the soil surface during rains. Under that measure, Iowa farmland loses an average 5.2 tons of topsoil per acre every year, according to the USDA's latest numbers, which are from 2007.

The USDA sees five tons per acre as a "magic number," Cruse said, because it's generally accepted to be the rate at which soil renews itself. So the prevailing view has been that "if we can limit erosion to five tons per acre, we can do this forever," Cruse said. But he added that the "best science" indicates that the real sustainable erosion rate is closer to a half ton per acre—meaning that even by the USDA's own limited measure, Iowa's soils are eroding much faster than they can be replaced naturally.

But here's where we get to the scary part. Using stereo-photographic techniques, Cruse and his team have been measuring a different form of erosion that occurs through what are known as "ephemeral gullies"—that is, large gashes in farm fields formed by water during heavy rains, bearing soil rapidly away and dispersing it into streams and rivers. This kind of erosion is not included in conventional soil-loss measures, and as a result, the USDA is "way underestimating" erosion in Iowa, he said.

Iowa Is Getting Sucked into Scary Vanishing Gullies

Friday, May 2, 2014

Daphne Miller - Farmacology on youtube

Dr. Miller long suspected that farming and medicine were intimately linked. Increasingly disillusioned by mainstream medicine's mechanistic approach to healing and fascinated by the farming revolution that is changing the way we think about our relationship to the Earth, Daphne Miller left her medical office and traveled to seven innovative family farms around the country, on a quest to discover the hidden connections between how we care for our bodies and how we grow our food.

Daphne Miller - Farmacology on youtube

Daphne Miller - Farmacology on youtube

Friday, April 25, 2014

Carbon Loss from Soil Accelerating Climate Change

New research has found that increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere cause soil microbes to produce more carbon dioxide, accelerating climate change. This research challenges our previous understanding about how carbon accumulates in soil.

Carbon Loss from Soil Accelerating Climate Change

Carbon Loss from Soil Accelerating Climate Change

Monday, April 21, 2014

No-Till Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates Published

For the past 20 years, researchers have published soil organic carbon sequestration rates. Many of the research findings have suggested that soil organic carbon can be sequestered by simply switching from moldboard or conventional tillage systems to no-till systems. However, there is a growing body of research with evidence that no-till systems in corn and soybean rotations without cover crops, small grains, and forages may not be increasing soil organic carbon stocks at the published rates.

No-Till Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates Published

No-Till Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates Published

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Climate Change and Desertification a Threat to Social Stability - UN

What is of higher value than being able to feed your family? For a significant part of the global population, this means having direct access to productive land – water, soil and its biodiversity – because land is their only tangible asset.

Some 500 million small-scale farmers support the livelihoods of over 2 billion people. More than 1.5 billion people live off degrading land; at least one billion are poor. The projected climate trends threaten their livelihoods.

Coping Mechanisms Disappearing

The frequency and intensity of extreme and unpredictable weather events, especially floods and droughts that are linked to climate change, is threatening their livelihoods. It is upsetting the coping mechanisms they have relied on in bad times, robbing them not just the ability to feed their families, but their dignity as well.

By 2010, 900 million people around the world faced chronic hunger, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report estimates that food demand will rise by 14 percent per decade while yields could decline by up to 2 percent per decade.

Land degradation is part of a toxic mix that is turning hungry people into vulnerable communities that are prone to instability, migration and conflict. It takes whatever underlying social weaknesses exist and magnifies them. For countries where social safety nets or alternative sources of income are lacking, underemployed and disenfranchised youth are the obvious targets of radicalization.

Let us be clear, food will be less plentiful or more expensive unless land stewardship on a global scale rises to the top of the international political agenda. In an interconnected world, a threat to food security is a threat to international security.

Climate Change and Desertification a Threat to Social Stability - UN

Some 500 million small-scale farmers support the livelihoods of over 2 billion people. More than 1.5 billion people live off degrading land; at least one billion are poor. The projected climate trends threaten their livelihoods.

Coping Mechanisms Disappearing

The frequency and intensity of extreme and unpredictable weather events, especially floods and droughts that are linked to climate change, is threatening their livelihoods. It is upsetting the coping mechanisms they have relied on in bad times, robbing them not just the ability to feed their families, but their dignity as well.

By 2010, 900 million people around the world faced chronic hunger, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report estimates that food demand will rise by 14 percent per decade while yields could decline by up to 2 percent per decade.

Land degradation is part of a toxic mix that is turning hungry people into vulnerable communities that are prone to instability, migration and conflict. It takes whatever underlying social weaknesses exist and magnifies them. For countries where social safety nets or alternative sources of income are lacking, underemployed and disenfranchised youth are the obvious targets of radicalization.

Let us be clear, food will be less plentiful or more expensive unless land stewardship on a global scale rises to the top of the international political agenda. In an interconnected world, a threat to food security is a threat to international security.

Climate Change and Desertification a Threat to Social Stability - UN

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

Farming for Improved Ecosystem Services Seen as Economically Feasible

Research conducted over 25 years shows that lowering -- or avoiding -- the use of chemical fertilizers in row-crop agriculture in the northern United States can reduce polluting nitrogen runoff, mitigate greenhouse warming, and improve soils while producing good crop yields. 'No-till' agriculture provided some similar benefits. The most effective regimes required that farmers adopt more complex crop rotations, but many indicated that they would accept payments to do so, and the public seems willing to pay.

Farming for Improved Ecosystem Services Seen as Economically Feasible

Farming for Improved Ecosystem Services Seen as Economically Feasible

Nutrient-Rich Forests Absorb More Carbon

Nutrient-Rich Forests Absorb More Carbon

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Will Increased Food Production Devour Tropical Forest Lands?

As global population soars, efforts to boost food production will inevitably be focused on the world’s tropical regions. Can this agricultural transformation be achieved without destroying the remaining tropical ecosystems of Africa, South America, and Asia?

Will Increased Food Production Devour Tropical Forest Lands?

Will Increased Food Production Devour Tropical Forest Lands?

Wednesday, April 2, 2014

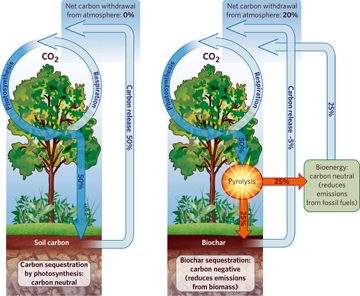

Doubt over the Use of Biochar to Alleviate Climate Change

In the first study of its kind, research has cast significant doubt over the use of biochar to alleviate climate change. Biochar is produced when wood is combusted at high temperatures to make bio-oil and has been proposed as a method of geoengineering. When buried in the soil, this carbon rich substance could potentially lock-up carbon and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The global potential of biochar is considered to be large, with up to 12 percent of emissions reduced by biochar soil application.

Doubt over the Use of Biochar to Alleviate Climate Change

Doubt over the Use of Biochar to Alleviate Climate Change

Deforestation of Sandy Soils a Greater Climate Threat

A new study finds that tree removal has far greater consequences for climate change in some soils than in others, a finding that could provide key insights into which ecosystems should be managed with extra care. In a comprehensive analysis of soil collected from 11 distinct U.S. regions, from Hawaii to northern Alaska, researchers found that the extent to which deforestation disturbs underground microbial communities that regulate the loss of carbon into the atmosphere depends almost exclusively on the texture of the soil.

Deforestation of Sandy Soils a Greater Climate Threat

Deforestation of Sandy Soils a Greater Climate Threat

Sunday, March 30, 2014

National Soil Collection May Unlock Mysteries, Research Possibilities 'Almost Limitless'

.jpg) A small army of researchers and university students lugging pick axes and shovels scattered across the country for three years to scoop samples into plastic bags from nearly 5,000 places. They marked the GPS coordinates, took photos and labeled each bag before mailing them back to the government's laboratory in Denver.

A small army of researchers and university students lugging pick axes and shovels scattered across the country for three years to scoop samples into plastic bags from nearly 5,000 places. They marked the GPS coordinates, took photos and labeled each bag before mailing them back to the government's laboratory in Denver.Though always underfoot and often overlooked, dirt actually has a lot to tell. Scientists say information gleaned from it could help farmers grow better vegetables and build a better understanding of climate change. A researcher of forensic science said mud caked on a murder suspect's boots could reveal if he had traipsed through a crime scene or had been at home innocently gardening.

David Smith, who launched the U.S. Geological Survey project in 2001, said data about the dirt will feed research for a century, and he's sharing it with anyone who wants it. "The more eyes and brains that look at it, the better," Smith said.

National Soil Collection May Unlock Mysteries, Research Possibilities 'Almost Limitless'

Monday, March 24, 2014

California Drought: Central Valley Farmland on Its Last Legs

Even before the drought, the southern San Joaquin Valley was in big trouble.

Decades of irrigation have leached salts and toxic minerals from the soil that have nowhere to go, threatening crops and wildlife. Aquifers are being drained at an alarming pace. More than 95 percent of the area's native habitat has been destroyed by cultivation or urban expansion, leaving more endangered bird, mammal and other species in the southern San Joaquin than anywhere in the continental U.S.

Federal studies long ago concluded that the only sensible solution is to retire hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland. Some farming interests have reached the same conclusion, even as they publicly blamed an endangered minnow to the north, known as the delta smelt, for the water restrictions that have forced them to fallow their fields.

The 600,000-acre Westlands Water District, representing farmers on the west side of the valley, has already removed tens of thousands of acres from irrigation and proposed converting damaged cropland to solar farms.

Many experts said if farmers don't retire the land, nature eventually will do it for them.

California Drought: Central Valley Farmland on Its Last Legs

Decades of irrigation have leached salts and toxic minerals from the soil that have nowhere to go, threatening crops and wildlife. Aquifers are being drained at an alarming pace. More than 95 percent of the area's native habitat has been destroyed by cultivation or urban expansion, leaving more endangered bird, mammal and other species in the southern San Joaquin than anywhere in the continental U.S.

Federal studies long ago concluded that the only sensible solution is to retire hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland. Some farming interests have reached the same conclusion, even as they publicly blamed an endangered minnow to the north, known as the delta smelt, for the water restrictions that have forced them to fallow their fields.

The 600,000-acre Westlands Water District, representing farmers on the west side of the valley, has already removed tens of thousands of acres from irrigation and proposed converting damaged cropland to solar farms.

Many experts said if farmers don't retire the land, nature eventually will do it for them.

California Drought: Central Valley Farmland on Its Last Legs

Monday, March 17, 2014

Climate Change Will Reduce Crop Yields Sooner Than Thought

Global warming of only 2 degrees Celsius will be detrimental to crops in temperate and tropical regions, researchers have determined, with reduced yields from the 2030s onwards. In the study, the researchers created a new data set by combining and comparing results from 1,700 published assessments of the response that climate change will have on the yields of rice, maize and wheat. Due to increased interest in climate change research, the new study was able to create the largest dataset to date on crop responses.

Climate Change Will Reduce Crop Yields Sooner Than Thought

Climate Change Will Reduce Crop Yields Sooner Than Thought

Can We Prevent a Food Breakdown?

As food supplies have tightened, a new geopolitics of food has emerged—a world in which the global competition for land and water is intensifying and each country is fending for itself. We cannot claim that we are unaware of the trends that are undermining our food supply and thus our civilization. We know what we need to do.

Can We Prevent a Food Breakdown?

Can We Prevent a Food Breakdown?

Thursday, March 13, 2014

Tropical Grassy Ecosystems Under Threat, Scientists Warn

Scientists at the University of Liverpool have found that tropical grassy areas, which play a critical role in the world's ecology, are under threat as a result of ineffective management.

According to research published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, they are often misclassified, and this leads to degradation of the land, which has a detrimental effect on the plants and animals that are indigenous to these areas.

Tropical grassy areas cover a greater area than tropical rain forests, support about one fifth of the world's population, and are critically important to global carbon and energy cycles, and yet do not attract the interest levels that tropical rainforests do.

Tropical Grassy Ecosystems Under Threat, Scientists Warn

According to research published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, they are often misclassified, and this leads to degradation of the land, which has a detrimental effect on the plants and animals that are indigenous to these areas.

Tropical grassy areas cover a greater area than tropical rain forests, support about one fifth of the world's population, and are critically important to global carbon and energy cycles, and yet do not attract the interest levels that tropical rainforests do.

Tropical Grassy Ecosystems Under Threat, Scientists Warn

A Tale of Two Data Sets: New DNA Analysis Strategy Helps Researchers Cut Through the Dirt

Researchers have published the largest soil DNA sequencing effort to date. What has emerged in this first of the studies to come from this project is a simple, elegant solution to sifting through the deluge of information gleaned, as well as a sobering reality check on just how hard a challenge these environments will be.

A Tale of Two Data Sets: New DNA Analysis Strategy Helps Researchers Cut Through the Dirt

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

Eroding Soils Darkening Our Future - by Lester R. Brown

In 1938 Walter Lowdermilk, a senior official in the Soil Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, traveled abroad to look at lands that had been cultivated for thousands of years, seeking to learn how these older civilizations had coped with soil erosion. He found that some had managed their land well, maintaining its fertility over long stretches of history, and were thriving. Others had failed to do so and left only remnants of their illustrious pasts.

Eroding Soils Darkening Our Future -- by Lester R. Brown

Eroding Soils Darkening Our Future -- by Lester R. Brown

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)